Father and son duo, Mark and Zane McMillan, began Uncle Charlie’s Tastes of Country earlier in 2022. The business was born out of a desire to connect consumers of their gourmet popcorn flavoured with native Australian ingredients with the peoples and stories of Wiradjuri Country, where their ingredients are sourced.

Now, almost one year later, they’re hard at work developing technologies to help other Indigenous-owned businesses share sovereign information to both Indigenous and non-Indigenous consumers: an important step in bridging gaps in knowledge and understanding between Indigenous-owned businesses and their customers.

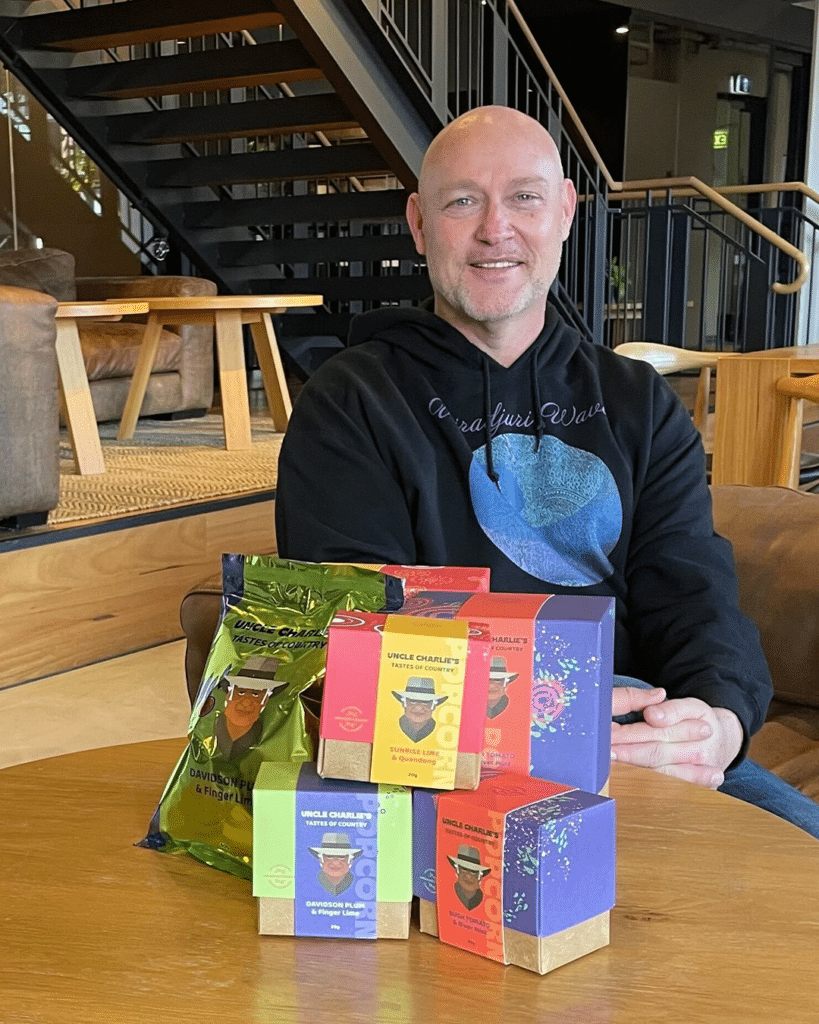

Mark was one of the 62 recipients of a Flexi-Impact membership in 2022, giving him access to a Hub workspace and cementing Uncle Charlie’s as an important part of our diverse business community.

We sat down with both co-CEOs to chat about how they’re leading the way in their impact-driven initiatives of their business, and what’s next on the horizon for Uncle Charlie’s.

Tell us a bit about Uncle Charlie’s.

Uncle Charlie’s shares the stories of Wiradjuri Country through our gourmet popcorn flavoured with Australian natives and botanicals, all sustainably sourced from the land.

With Uncle Charlie’s, we wanted to make a business that was a family business and an Indigenous-owned business. Uncle Charlie Evans was a proud Wiradjuri man born at Peak Hill at the turn of the 20th Century. One of his siblings is our Nan – Daphne Barnes.

We knew that we wanted to weave together stories about our family, and use the popcorn as a medium to tell Australian people stories from different nations about the native ingredients that we’re using. Above all else, we wanted to operate Uncle Charlie’s with a focus on good ethical decisions.

What kind of ethical initiatives do you engage with?

We redistribute 5% of our profits to the nations where each of our raw ingredients comes from, ensuring all of the ingredients are sustainably sourced and harvested.

From the outset, we wanted to always be clear about whose Country offered the products up. Rather than just asking ‘who are the people of the Country?’, we’re asking ‘what is the Country that the ingredients in our popcorn are coming from?’. We want to communicate more than who the rights holders are, and actually delve deeper into connections to the land and give the people of the Countries the chance to tell their stories.

We’re currently in the process of developing technology that will allow us to communicate this information and these stories to the end consumer, showing people with certainty where everything came from. That’s our sovereign obligation as an Indigenous business.

Can you elaborate a little more on how you’re using technology to help you with this mission?

We’re working with a number of tech companies to track sovereign information. What we’re currently developing is a QR code system that communicates geolocation data – which nation the ingredients are from, what crop they’re harvested from, that sort of thing.

On our end, that allows us to ensure the profits go back to the right people. This drills right down to even the water that’s used to grow the corn. We want to challenge the status quo about how we think about who is offering up the things we eat.

We’re working with the developers to have more of a focus on UX, and how we want this information to be presented. It’s really important that non-Indigenous customers can understand what has always been – these aren’t new things, this information has always been there, we’re just packaging it up. This is an act of sovereignty, that you continue to welcome people to your Country. This is us honouring Uncle Charlie’s way.

The packaging of your products is really eye-catching, what’s the story there?

The packaging and design of our products have all been done by Prue from Ography Design. The colour palette was made by combining images from Wiradjuri Country, pixelating them, and pulling the colours from the result. She came up with the idea of the box opening up to a Coolamon, so you can eat the popcorn out of it and share it around. If you pop out the lids on the boxes, you’ll see the designs match up to where the fruit and spices are grown across Australia. There’s no glue used on the packaging, and the materials are all environmentally friendly.

Ultimately, the packaging is the culmination of non-Indigenous and Indigenous design working together. She took her design and aesthetic and made it speak to Indigenous people. It’s incredibly empowering for non-Indigenous creatives to alter their practices to be better people.

We wanted to make it very clear in the design process that this isn’t just packaging, this is a three-dimensional invitation that supports non-Indigenous people’s emotional step into a relationship with Indigenous people.

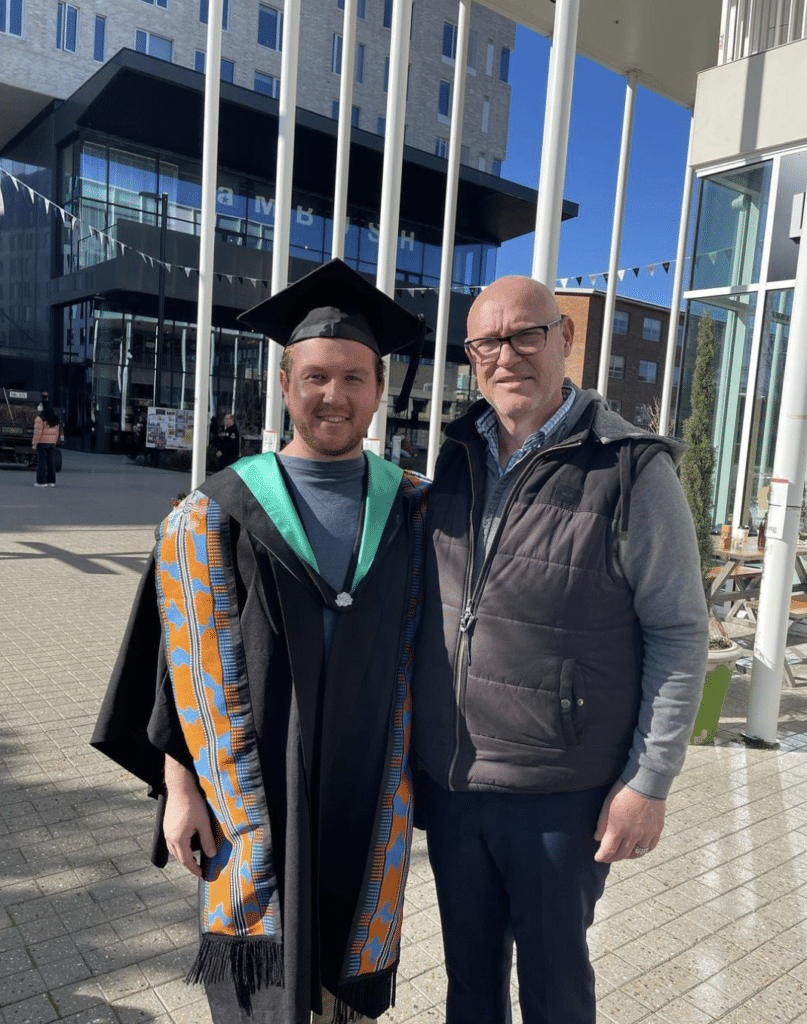

Zane, you’ve just graduated from university. What has your day-to-day looked like at Uncle Charlie’s since?

It’s been busy! One of the first things I had to organise was getting more stock to our stockist, Gourmet Brands. Then I headed to a trade fair, working five days at the stall. We got a lot of good exposure from that.

After that, I came to Coolamon, which is where we get all of our ingredients sent to and where we hand pop, hand season, and hand seal the popcorn. Then it all gets sent to Melbourne, where the packages are assembled in their beautiful boxes.

What are you currently working on? And what’s next for Uncle Charlie’s?

We’re currently working on developing a new popcorn flavour, on top of the three that we already have. We’re also working on a spice rack where we’ll just sell the popcorn flavouring as is, to use on food. Eventually down the line, we want to start making tonic water that’s infused with native flavours, and DIY popping kits so people can pop and season their own popcorn.

With all of these developments, we want to build them around the Wiradjuri seasons, and select flavours that are evocative and gourmet.

The impact of Uncle Charlie’s on our family has been profound. One of the greatest things has been getting to work together as a family. If you would have asked me to do this 10 or 20 years ago, I wouldn’t have done it. I was so angry. Indigenous lives are difficult because of certain things, but you know, if we think about 80,000 years of history and put that against the past 250 years, to survive means more than just thinking about our current life as Indigenous people. To survive means asking ourselves ‘where do we fit in that 80,000 years?’